Every year around half a million tourists pack themselves onto the 21 square kilometer island of Koh Tao. With so many people filling such a small space it’s no surprise that the waste and pollution produced by all these masses exceeds the capacity of our island’s landfills and waste management facilities. The Government of Koh Tao and other groups like Save Koh Tao have been heavily involved in trying to solve these challenging problems, but with so many transient tourists knowing (and even caring) little about this beautiful island, it is difficult to keep everyone acting conscientiously. The spirit of the Save Koh Tao Festival is to bring the community together to show those that visit the island just how much people living there care.

With that in mind, the Save Koh Tao Festival held their first Trash Sculpture Competition in 2017, encouraging dive schools around the island to take part in raising awareness against the use of plastics and move towards more sustainable alternatives. We were also encouraged to create sculptures that could then be transformed into artificial reef structures, an opportunity too tantalizing for us to pass up for us Conservation Divers.

For our sculpture, we wanted to help raise awareness for a marginalized group of organisms that are now rarely observed on and off the reefs of Koh Tao – the Seahorse. Despite their protection under CITES, the global trade of seahorses is estimated at around 15-20 million individuals per year, with Thailand being one of their largest exporters. Many of these endangered creatures end up in Chinese markets where they’re used in antiquated holistic remedies no more effective than a sugar pill, and yet the trade continues. Threatened by over-collection and pollution, it’s hard to miss the irony of a Trash Seahorse decorated in plastics and nets, the very objects that are destroying their habitats and pushing them towards extinction.

Not So Fantastic Microplastic

Marine debris and waste comes in many forms, affecting coral reef ecosystems in a variety of unpredictable ways. One of the most lasting is plastics. A study conducted in 2014 by Cózar et al. suggested that the current load of surface plastics in our planet’s oceans ranges anywhere from 10,000-40,000 tons. Much of this is made up of microplastics, often times only observable through – you guessed it – a microscope. Microplastics are the legacy of the many plastics that we use in our day to day lives. The breakdown of large plastic products like bottles and straws into microplastics can take a remarkably long time. Estimates suggest that certain plastics can take up to 600 years to be broken down, but much of this remains up to speculation due to the complications presented when they’re introduced into marine ecosystems.

Plastics degrade as they are bombarded with ultraviolet B radiation which causes them to become brittle. This allows them to be broken down into smaller and smaller pieces of plastic, eventually becoming microplastics. It’s this same form of radiation that helped cause the mass coral bleaching event that swept across our planet’s coral reefs this year. In the ocean the degradation of plastic can take significantly longer, as smaller amounts of UVB radiation reach the plastics, particularly the ones that sink down to the depths of our oceans. The plastics that float along the surface also receive protection from UVB radiation, but in a very different way. Floating surfaces are hard to come by in the open expanses of our oceans, but buoyant plastics provide just that base for light loving organisms to thrive. Filamentous algae begin to grow over the plastics taking advantage of the light they now have access to, sheltering the plastic from much of the radiation that was breaking it down.

These plastics can be so long-lived in our ecosystem, that they’ve accumulated in incredible volumes in our planet’s ocean gyres. Many of you have probably heard of The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, one of the more infamous gyres that has amassed so much plastic that it conjures up images of a floating plastic country. These ocean gyres are the result of the Earth’s tilt, which causes winds and currents to travel clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere and counter-clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere. This is known as the Coriolis Effect and it’s responsible for the collection of buoyant plastics into these startlingly high concentrations. While the Coriolis Effect concentrates plastics on an oceanic scale, pieces of plastic attract man-made materials on a microscopic scale. Toxic chemicals and pollutants found throughout our planet’s oceans attach themselves to the surfaces of microplastics as though they were magnets, making them even more dangerous to the fragile ecosystems in which they’ve become ubiquitous.

Many of these plastics which are covered in toxins, algae or even just brightly coloured get mistaken by marine life as food and ingested. As microscopic plastics build up inside of small organisms like zooplankton, not only can they not digest the plastics, but it also begins to affect their ability to control their buoyancy. The weakened zooplankton become an easy target for larger predators and now the seemingly immortal plastics that caused the death of their previous host find a new home to destroy. These plastics cycle up the food chain in this way until the creature in which they’re stored dies and decomposes, returning them back into the ocean on their perpetual, indifferent quest of death. This terrifying process is known as bioaccumulation and it can have devastating effects that ripple throughout entire ecosystems, affecting creatures even as mild mannered as a seahorse.

The Long Journey of the Trash Seahorse

The trash we collected for our sculpture was collected from the garbage heap at the top of Taa Cha’s jungle steps, an eye sore that we have to pass by every day before dives during the low tidal season. The structure was covered in translucent fabrics and plastics, allowing the lights that were passed through it to make it glow at night. For a sculpture covered in garbage, it didn’t look too trashy!

Fortunately, many festival goers appreciated the hard work that was put in and the sculpture was lucky enough to take the 10,000 baht top prize, despite some very creative entries from the other dive schools. The money was used to show our appreciation to the students and interns that helped us put together the festival and the rest of the money went towards our Artificial Reef Program, helping to fund our future artificial reefs.

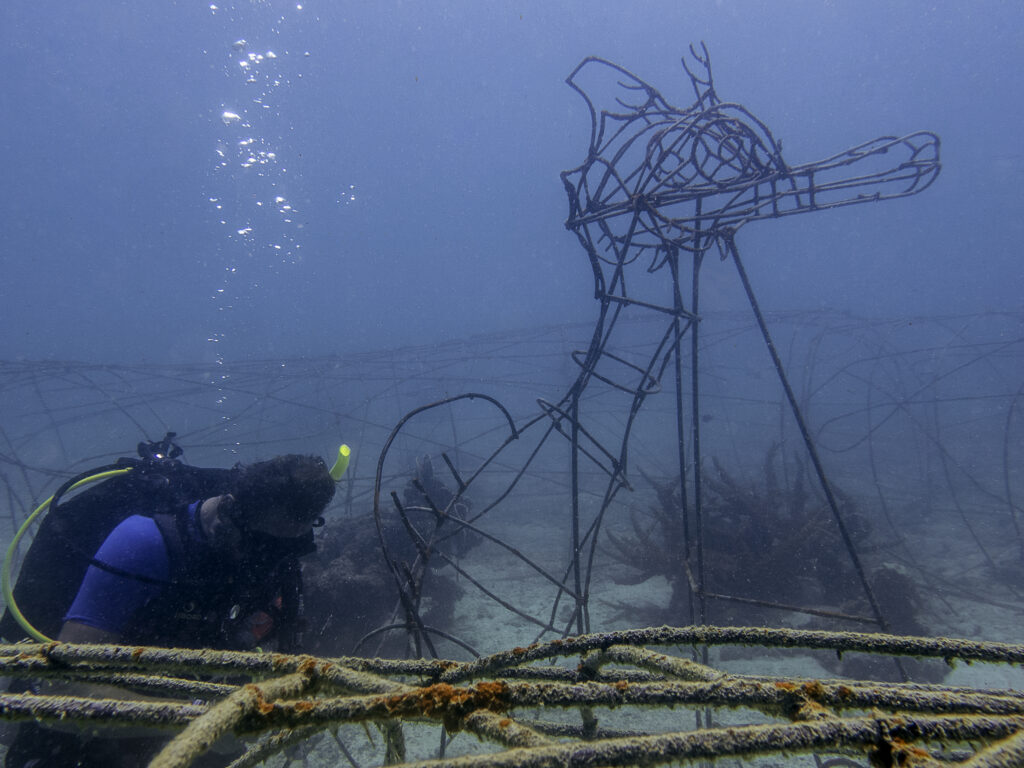

The Trash Seahorse is deployed in Ao Leuk, recieving a low impressed electrical current from Coral Aid’s NETV3 Duo. Electrifying our seahorse will help strengthen it as an artificial reef and improve it as a home, making it easier for naturally fragmented corals to grow on its bars. Making use of technological advancements in reef restoration such as this is crucial if we are to stand a chance at protecting our planet’s coral reefs for future generations.

This evolution from inorganic materials to organic alternatives underpins the philosophy of sustainable development. In time, what was once a sculpture covered in trash will become transformed into a living, breathing structure, providing a home for thousands of diverse lifeforms.